By Tim Mumford, IPA Australia

In the context of capital projects, ‘governance’ is a term that is frequently used but rarely understood.

Governance should be thought of as the rules and mechanisms for directing and controlling investment in capital projects. This includes – but is not limited to – decision making, due diligence, portfolio management, opportunity shaping, benchmarking, risk appetite, project delivery, and continuous improvement.

Effective governance is even more difficult – it is a combination of doing the right project(s) and doing those projects right. Disharmony between these two elements results in project benefits not being maximised. Unfortunately, this is often true: most capital projects fail to achieve the proposed value promised at authorisation. Future cash flows (or benefits) are often less than expected, capital costs are higher, and schedules are longer. In terms of numbers, the average project’s net present value (NPV) degrades by 22% between approval and completion. (Barshop, 2016) Poor governance plays a major role in this degradation and, looking to the future, will require a higher degree of focus than we’ve previously employed. (VictorianAuditor General, 2015)

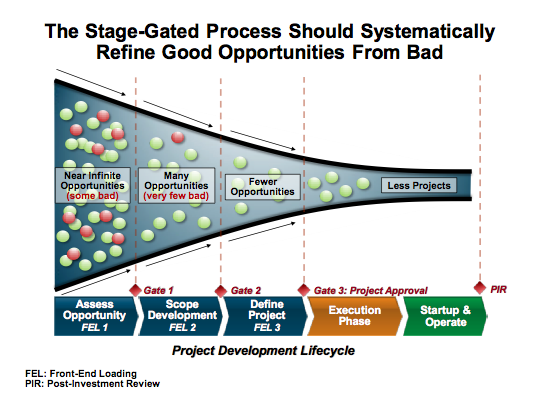

When looking at the performance of infrastructure projects, it is clear that effective governance is systematically difficult to achieve. Project assurance is one such way in which organisations struggle to deploy governance. Frequently, organisations do not employ a stage-gated opportunity shaping process that is prescribed by most – if not all – large project management institutions [ED1][TM2]. The stage-gated process governs the shaping of opportunities into projects using clearly defined phases; this shaping process allows decision makers to kill projects that are not beneficial or not aligned with council’s strategy before too much money is invested in their development.

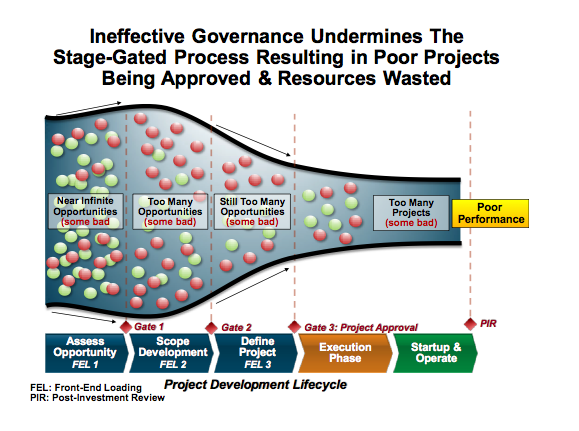

By using a stage-gated process limited capital can be directed to the best opportunities. If a stage-gated process is employed, often it is not rigorous or strong enough to stop bad opportunities before they become projects (i.e. the ‘gates’ are always open). A good litmus test for effective governance is inspecting the magnitude of opportunities with respect to the organisation’s project development lifecycle.

As seen above, ‘good’ opportunities should – via the stage-gated project delivery framework – be systematically separated from ‘poor’ ones; further, they must align with the council’s priorities, objectives, budget, resources, and competencies. Poor opportunities are often progressed too far wasting valuable (and often limited) resources. Fortunately, symptoms of ineffective governance are relatively easy to identify.

From assessment and benchmarking of hundreds of project portfolios, it is clear that gatekeeping, as the final output of an organisation’s governance process, is the key driver of overall portfolio performance. (Garland, 2009) Specifically, organisations that approved too many opportunities during FEL 2 are victim to those same opportunities either a) being recycled back into the system draining resources, or worse, b) approving the opportunity only to realise that it was not the ‘right project’ and not executing it. Based on learnings from governance research, an ineffective or undermined governance process often have some (if not all) of the following symptoms:

1. Most (greater than 30%) of the projects in the portfolio are schedule-driven

2. The project sponsor (the person accountable for the economic [or otherwise] benefits of the project) is the ‘gatekeeper’

3. Project process is bypassed, or a considerable portion of

theproject’sexecute funding is ‘pre-approved’ (considered defacto authorised)

4. Contractors are solely responsible for the scoping, definition, and/or execution of the project

5. Competitive tendering is relied upon for delivery of capital effective scope

6. Scope is dropped (or added) after Gate 2 (or later)

7. Deliverables and answers

requiredto makea decision on the feasibility of an opportunity progressing are waived till the next phase

8. The organisation places a very high degree of emphasis on project predictability (over project effectiveness)

Governance requires leadership; responsibility and accountability must be appointed in unison. (Merrow, 2011) In the context of local

government this is difficult and can be attributed to short election cycles (state, federal as well as local), the relatively long

durationbetweendecisions being made and the outcome of those decisions, the fact that capital works are multi-functional in nature, and that undeniably projects are subject to exogenous events. In totality, these provide plenty of opportunities for sub-optimal outcomes to be justified. Notwithstanding these barriers, there are organisations that, through effective governance, consistently deliver successful capital projects. Interestingly, the leaders of these organisations will always be able to answer the question (for each opportunity): “What is the best way to take advantage of this opportunity that will maximise benefit?”.

For other project organisations, answers to this question are often difficult to verbalise. Fortunately, creating actionable objectives isn’t fraught with too much difficulty:

1. Objectives must align with organisations short and long-term strategy

2. Objectives must be comprehensive, tangible and measurable

3. Project teams must understand these objectives

4. Trade-offs between priorities must be stated (i.e. you cannot have your cake and eat it too).[TM3]

Projects that have clear objectives routinely deliver better project outcomes. (Allport, et al., 2008, p. 152) Satisfying these credentials requires strong leadership which stems from good project governance.

The discussion is further contextualised by the fact that councils, as opposed to private industry, are not profit driven and do not have (traditional) shareholders. Irrespective of this difference, councils do have stakeholders – their community –, and these citizens have an expectation that projects executed by local government are delivered in a capital effective manner. While the differences between the two may seem wide, the philosophy on capital projects are nearly identical: both private industry and local government want to maximise benefit.

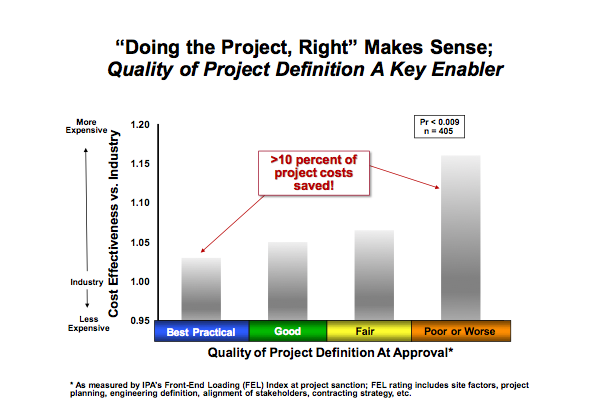

As seen above, a clear statistical indicator of capital effectiveness, and one of the final aspects of effective

projectgovernance,is project definition. Specifically, quality of project definition is the best indicator of whether that same project will deliver superior project outcomes (cost, schedule, operability, and safety). Organisations with weak governance will systematically approve projects with sub-optimal project definition, and in turn, pay more capital for the same scope than their peers. This effectively means that fewer opportunities can be delivered for the same budget. Akin to shareholders of large organisations, citizens are looking

forreturnon capital employed. While the return may be slightly different, the principles of effective governance remain the same.

About the author: Tim Mumford, Consultant at Independent Project Analysis (IPA) Australia, has critically evaluated the drivers and outcomes of over 100 capital projects spanning a wide range of industries: infrastructure, manufacturing, oil & gas, refining and mining and minerals. These projects range in complexity (floating LNG to car parks) and have been executed over a wide-range of continents. Tim has also analysed the drivers of successful portfolio management and project governance. About IPA: Independent Project Analysis (IPA) is a global research organisation that partners with organisations to improve the definition and delivery of capital effective projects, project organisations and teams, and effective structures of project governance. Over the past 25 years IPA has critically and statistically evaluated over 17,000 projects of various sizes and complexities across a wide range of industries from both private and public organisations.

About the author: Tim Mumford, Consultant at Independent Project Analysis (IPA) Australia, has critically evaluated the drivers and outcomes of over 100 capital projects spanning a wide range of industries: infrastructure, manufacturing, oil & gas, refining and mining and minerals. These projects range in complexity (floating LNG to car parks) and have been executed over a wide-range of continents. Tim has also analysed the drivers of successful portfolio management and project governance. About IPA: Independent Project Analysis (IPA) is a global research organisation that partners with organisations to improve the definition and delivery of capital effective projects, project organisations and teams, and effective structures of project governance. Over the past 25 years IPA has critically and statistically evaluated over 17,000 projects of various sizes and complexities across a wide range of industries from both private and public organisations.

References:Allport, R., Brown, R.,Glaister ,S. & Travers, T., 2008. Success and failure in urban transport infrastructure projects, London: Imperial College London.Barshop, P., 2016. Capital Projects: What Every Executive Needs to Know to Avoid Costly Mistakes and Make Major Investments Pay Off, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.Garland, R., 2009. Project Governance: A Practical Guide to Effective Project Decision Making, Kogan Page.Victorian Auditor General, 2015. Local Government: 2014-15 Audit Snapshot, Melbourne: VictorianAuditor General.