A project that is transforming barren land scarred by acid sulfate soils into an ecologically diverse wetland has become an exemplar study for remediating wetlands and agricultural landscapes.

The award-winning Big Swamp project saw Greater Taree City Council (GTCC) join forces with researchers from University of New South Wales, to rehabilitate 700ha of acid sulphate soils (ASS) into tidal and freshwater wetlands.

The Big Swamp area, part of the Manning River catchment, represents 2000ha of coastal floodplains. The area was drained extensively in the early 20th century during a public works program that aimed to reclaim the land for agriculture

(which failed), and as a result has been widely recognised as one of the worst acid hotspots in the country during the past 30 years.

MidCoast Council's Environmental Services Team Leader Tanya Cross says the site had become synonymous with poor water quality, acidic drainage and bad land management.

“It was no accident that both the NSW Acid Sulfate Soils Advisory Committee and the National Committee for Acid Sulfate Soils chose photos of Big Swamp for the covers of their primary publications – this area was generally recognised as one of the worst ASS ‘hot spots’ on the entire NSW coast,” she explains.

“Prior to the project commencing large fish kills were recorded in the estuary and acidic plumes were measured more than 10km downstream of the site.”

In 2011, the council received a $2 million Federal Government grant, and engaged UNSW’s Water Research Laboratory (WRL) to prepare a hydrological study for the Big Swamp.

The WRL is a non-profit water engineering organisation, with Australia’s largest hydraulic laboratories at its disposal.

In November 2013, the first stage of the Big Swamp Restoration Project was completed – with outstanding results. The large, restored wetland is now a functioning ecosystem, with significant improvements to surface and groundwater pH, raising discharge waters from approximately 3.5 (which is similar to tomato juice) to circum-neutral levels (around 6.5, or near pure water).

The project was recognised with a coveted

Green Globe Award in 2015, and is held up as an exemplar of how to remediate ASS in agricultural landscapes.

Restoring Big Swamp

Acid sulfate soils are a major problem in Australia, with about five million hectares of the country affected.

The Department of Agriculture and Water Resources says that when acid sulfate soils are disturbed or exposed and react with oxygen, they produce sulfuric acid. Metals may be released from sediments and become bioavailable in the environment, oxygen may be removed from the water column and gases such as hydrogen sulfide and sulfur dioxide and methane may be released.

WRL Principal Research Fellow Dr Will Glamore, who undertook the study, says there is no quick-fix for acid sulfate soils. Given that acid is generated when these soils are exposed to air, re-wetting the soils is often the answer.

“The best way to fix them, long term, is quite simply to restore them back to the way they were,” Glamore explains. “That means pulling out the levees, ripping out the floodgates and getting the tide back into the site.”

WRL’s Big Swamp Hydrological Study identified acid hotspots, transport pathways and flooding issues, and nominating high-priority areas for remediation.

The site was redesigned as a tidal and freshwater wetland. The 700ha site now includes a 80ha tidal wetland that was created by reforming a series of cattle grazing paddocks, infilling 15kms of deep drains and designing a new, large tidal creek.

The 620 ha freshwater wetland included the reshaping of the landscape to encourage re-flooding of large areas of the site, redesign of flood mitigation drains, drain infilling to reduce acidic discharges, and the decommissioning of a large levee structure to ensure hydrological connectivity.

So far, the council has purchased 700ha of private land for the project.

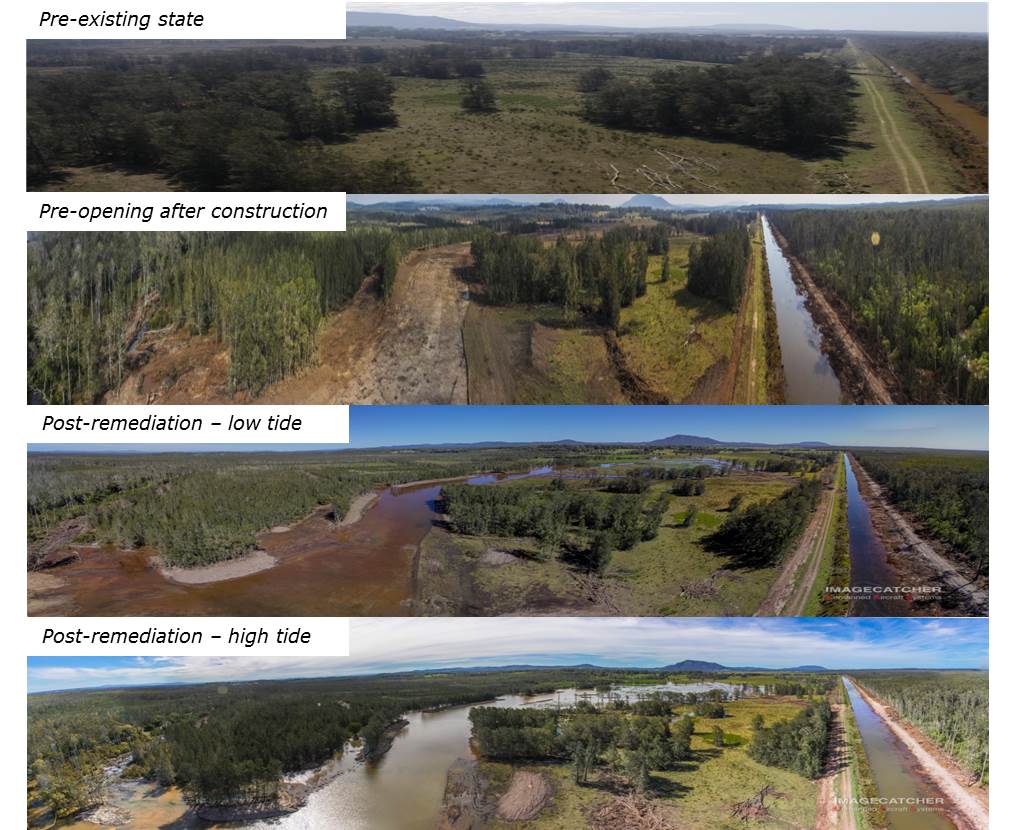

Innovation was introduced into the project through the use of unmanned aerial vehicles during the planning and evaluation phases of the project, the images from which were used to communicate the extent and state of the site, as well as scientifically map the landscape changes and hydrology.

Climate change was integrated into every stage of the remediation strategy and has resulted in one of the first large scale restoration projects that considers the implications of sea level rise and changes in salinity dynamics within on-ground plans.

However, Cross says the project’s success can be largely attributed to its collaborative approach, both with the community and with researchers.

Glamore was full of praise for the council’s dedicated approach to the project.

“Working with a Council that’s interested in learning from experience and constantly improving is fantastic and definitely WRL's preferred method of working,” Glamore says.

“The council put someone on the project full-time, which is unusual, and although this person didn’t have a scientific background, they were willing to be trained in the science and report the findings back to the council.

“Then the council, in turn, were flexible enough to adapt the plan to suit the findings. Not everyone is willing to do that; people will often say, ‘Here’s what you’ve said from the beginning, let’s just roll that out.’

“Secondly, the council was willing to take risks in buying this land. At a time when many councils are trying to get rid of assets, this council said, ‘No, this is such an important problem that needs fixing, we’ll take on the land management, we’ll take on the long-term tenure’.”

Community consultation

Initially, the community was hell-bent against the project, even having a petition against it tabled in the NSW Parliament.

Glamore says undertaking thoughtful communication with the community was integral to the project’s success.

“[An approach] I personally find very successful in getting the community engaged, is meeting people in small groups,” he says.

“Instead of having 50 people at one meeting – which is normal in these types of projects – I prefer having five meetings with 10 people. That may involve visiting the different interest groups, or even going to have a cup of tea at a concerned resident’s house, which we did a lot of.

“For most of the landholders, you can’t have a group meeting and expect them to say anything, but they will chat with you if you’re standing together in a paddock on their land. It’s a lot more time-consuming, but the results are a lot better.

“It was important to say: “We’re going to use science to lead this process, to show the community that we can do something beneficial. In fact, it’s going to make life better, not worse.”

Cross says some of the key learnings from the project were:

- The importance of effectively communicating the problems of acid sulfate soils in a way that was easy to understand;

- Involving landowners in developing studies and decision making;

- Making the issue a whole-of-community issue, not just an individual landowner's problem;

- Creating a partnership approach and working together for a common goal, which was the health of the estuary; and

- Utilising the passion of community members to make a difference.

Flow on effects

The Big Swamp research presented WRL with some significant and transferable findings.

“After 18 months of on-ground sampling I knew the project had some fascinating research possibilities, which I was keen to explore,” Glamore says.

“When a large flood came through the land, we pushed hard for the University to invest resources into monitoring that flood and tracking the acid plumes.”

This research was instrumental in demonstrating how acid runoff was destroying oysters and fish life downstream of the Big Swamp area.

“This not only made headlines in the national press, but was a key trigger in getting the local community involved so they were willing to sell their land and we could get on-ground restoration work underway,” Glamore says.

Glamore says while WRL initially won the tender to help prepare the hydrological study, once the flood had come through and the on-ground work was underway, they applied for and won another couple of grants to progress the project.

“Council started winning grants and it just got bigger and bigger,” he says. “Now we’re collaborating with Council on a whole bunch of other work, with a lot more money. It’s probably the biggest coastal restoration project in the state right now and we’re hoping to double it!”

MCC and WRL have commenced a long term monitoring program which includes a three year, intensive water quality program, six monthly GPS repeatable aerial photographs using a drone to capture landscape change, a vegetation monitoring program, and a photogrammetric survey using a drone at high and low tide to measure the volume of tidal water entering the site.

The project has become a demonstration site for wetland restoration across NSW, with state-wide demonstration and science days organised onsite.

The Big Swamp Restoration Project is recognised as providing valuable learnings about broad acre remediation of acid sulfate soil disturbance in wetlands and agricultural landscapes.

When undertaking the project, WRL invented an evidence-based priority method to inform on-ground decisions based on targeted field data collection exercises. This innovative method ensured that every dollar spent on the landscape restoration was justified and science based, and is currently being applied at other locations across NSW.

New scientific methods were also developed to understand how the entire estuary functions and the role of the proposed restoration works to the entire catchment. This novel approach helped determine the optimal restoration techniques, as a range of measures were identified to ensure the health of oyster leases more than 10 km downstream of the restoration site.

Cross says these learnings will encourage best practice management of ASS landscapes in other affected areas.

“The Northern Rivers Local Land Services brought a group of landowners from the Clybucca catchment area near Kempsey to Big Swamp to see firsthand the results of the project and what can be achieved,” she says.

Image 1,2: Greater Taree City Council

Image 3: University of New South Wales. UNSW's Dr William Glamore (right).