Chris Sheedy

From the main streets of Maitland and Taree to the war-ravaged devastation of Mogadishu, Greg Blaze OAM has experienced equal amounts of struggle and satisfaction during his adventurous civil engineering career.

There is something very special about working in civil engineering, says Greg Blaze OAM, and it has to do with the fact that you’re always witnessing the effect your work has on the community. Sometimes, particularly during construction, that might be a negative effect as shopkeepers, business people and locals are bothered by the intrusion into their daily lives. But once each project is complete, there is almost always a satisfactory ending for everybody involved.

“People might struggle during the project, so we try to help them by communicating effectively and regularly,” Blaze, an author, humanitarian engineer with RedR and the United Nations, and currently working as a Civil Engineer with MidCoast Council in NSW. “We face many challenges as the job moves along but at the end of the project people see what you’ve done. It becomes something that everybody uses every day, and they say, ‘Oh gee, that’s nice!’.”

Then there are places that he has carried out similar work but where extremely serious problems exist, such as Somalia, a nation that is mostly ruled by warlords. Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade warns travellers, “Do not to travel to any part of Somalia because of armed conflict, the ongoing very high threat of terrorist attack and kidnapping, and dangerous levels of violent crime … There is no effective police force in Somalia; lawlessness, violent crime, clan violence, banditry and looting are common.”

Despite the warnings, Blaze originally accepted a three-month posting through RedR. During his in-country visits he was often protected by small armies of local militia.

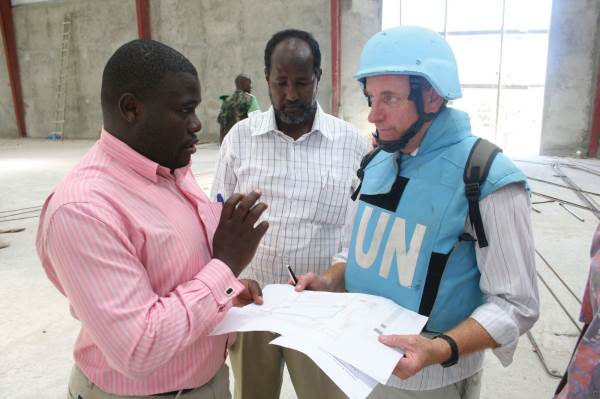

“At one stage I had 60 gunmen looking out for me, on one of the missions,” he smiles. “I was managing the contract process for the building of a warehouse for aid provisions. You’ve got a war going on and aid organisations are trying to get food to people. They would normally house their food in warehouses in the city, but the capital Mogadishu was too dangerous, so a warehouse was required to be built in a protected area within the port.”

That role snowballed into several others, as organisations such as the UN reached out to Blaze, one of very few civil engineers in Somalia. He was asked to do road and bridge inspections and to set up contracts for re-gravelling and re-building. The three-month stint soon blew out into a five-year odyssey.

“I lived in Nairobi and flew in and out of Mogadishu,” says Blaze, a keen surfer who has also authored two books – There Are No Waves In Mogadishu and Encounter With the Christ. “I would work six-month stints then take a couple of months off. It was a very interesting change, and it was a very satisfying.”

One of the projects he was asked to oversee was the clearing of four sunken ships from Mogadishu’s harbour. The wrecks were blocking three of the six berths in the port.

“I’m an engineer, but I hadn’t done any salvage work before,” he says. “But I was the only engineer there, so I put together some contracts and talked to people who do these sorts of things. Meanwhile, a war is going on around us. But we did it. We cut the vessels up and lifted them out. We dredged the port, too. The port is now operating at 100% capacity, not only for the humanitarian cargo, but for general cargo for the whole community.”

During that five-year stay, Blaze had an experience that neatly summed up all of what he felt about the reason he was working in such a place. It occurred when he was visiting a refugee camp in the north of Somalia, one that had been set up by humanitarian aid organisations.

“The accommodation in the camps was in shanty tents, made out of stick structures on hard stony ground, often covered with cardboard and pieces of plastic, and these would house families of around six people,” he recalls. “We went to a sort of medical centre and on a table in the middle of the room was a little boy, maybe three years old.”

The boy was starving and looked as if he was dead, Blaze says. A tube ran into his nose, slowly feeding nutrients into his body. His mother sat in the corner, staring into space. Her mouth hung open as flies swarmed around.

The doctor told Blaze that the mother had just carried her son for 12 days from the war zone to get to the camp. She was clearly malnourished and in shock. The tube in the boy’s nose was feeding him a substance called plumpy nut, a peanut-based paste formulated for treating severe malnutrition. Within three weeks, the doctor said, the boy would be on his feet again, running around happily with other children.

If Mogadishu’s harbour had not been cleared of scuttled ships, the doctor continued, the UN’s World Food Programme in Somalia would have found it very difficult to transport supplies of plumpy nut. Blaze’s salvage work in Mogadishu had an effect on this boy’s chances of survival.

“I enjoy knowing that I’m doing the engineering work that in some way contributes to such outcomes,” Blaze says. “In many ways, as civil engineers we make outcomes more suitable or positive for real people in real communities. That appeals to me, no matter where I am in the world.”

Delivering resilience

From angry shop-owners on the NSW mid-north coast to starving families in Somalia, Blaze has seen it all. His experiences have taught him a great deal about resilience during a career in which inventive solutions are often required to overcome seemingly insurmountable challenges.

Have you changed, as a person, as a result of your humanitarian work?

I’m sure it has impacted and affected me. It has made me realise that local government engineers have a lot more skills than they think. They have technical skills to deal with specific issues for which they’re trained, but they also think and work at a level that gives them other great skills. It might be talking to politicians, or communicating with the public, or promoting ideas to a community. That’s why local government engineers are easily able to transfer their skills into the humanitarian sector. It is very satisfying work and can even strengthen the engineer’s skill base for a return to the local government sphere.

What has it taught you about resilience?

On the community side, it’s important to realise that civil engineers carry out their work to make communities more resilient. Whether it’s bringing food to starving refugees or upgrading a main street so a town doesn’t die, we are in the business of resilience. On a personal level, it has taught me to not sweat the small stuff. We really do worry about some silly rubbish.

Is every civil engineering project just a mini war zone, with an enduring peace at the end?

Yes, I guess you could put it that way! Actually, I presented a paper on that at a conference. I’d returned from Mogadishu to Maitland and my presentation’s theme was ‘Same thing, different place’.

What can engineers learn from your lessons?

One project we did in Maitland, turning a main street into a one-way shared zone, originally made some people unhappy. A part of the community didn’t want it. But the council had spent $10 million to help build the city’s resilience and, if it wasn’t upgraded, that part of the town would have died. Everyone would instead go to the big shopping malls. A small protest was organised and a young engineer working with me was quite upset about it, as he knew that we were doing a good thing for the city, and for these very people. I told him it’s not worth worrying about, and in fact we should celebrate the fact that we live in a country where you can actually protest without having to carry machine guns