A neglected source of energy is flowing beneath our cities and towns, with the potential to deliver sustainable heating and cooling while slashing energy and water use.

Wastewater is a reliable source of thermal energy, which, unlike energy sources like solar or wind power, is largely independent of external forces. In Melbourne there is enough thermal energy in the wastewater to provide heating/cooling for up to 2000 commercial buildings. Using this resource could help the city take a big step towards its goal of being carbon neutral by 2020.

However, outdated regulations, a siloed industry and the perception of risk have stymied the large-scale rollout of projects.

However, outdated regulations, a siloed industry and the perception of risk have stymied the large-scale rollout of projects.

The case for utilising the untapped potential of wastewater will be presented in August at IPWEA’s Sustainability in Public Works 2016 Conference in Melbourne.

Presenter Nick Meeten, who is a Sustainability Consultant from New Zealand-based Smart Alliances, has more than 20 years’ experience in urban infrastructure, project management and energy recovery solutions. He formerly worked for German-based HUBER as Green Buildings Team Leader.

Around the world, there are close to 500 established systems that recycle the energy from wastewater for heating and/or air conditioning. Meeten says the science is already in on how efficient such systems are.

“Even though that idea may seem to be new and innovative and by association seem quite risky, technically it’s actually very simple,” he explains. “The oldest ones were done back in Switzerland more than 20 years ago.”

“It’s using robust equipment and very sound basic engineering concepts – the risk associated with these projects is very low.”

Research

To support the claims on how efficient the systems are, Meeten points to an American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) study, which looked at the benefits of using a geothermal-heat pump (GHP), compared to a variable-refrigerant flow (VRF). While the water source differs, Meeten says the research is still applicable.

“Wastewater is just another source of water, which has all the same basic characteristics – it’s a bit dirtier, but in terms of its ability to provide heating or cooling, it’s exactly the same,” he says.

The two-year study compared GHP and VRF systems installed on different floors of the ASHRAE headquarters buildings. With all variables accounted for, the study found that energy use by the GHP averaged 44% less than the VRF system.

How it works

One of the most common misconceptions about utilising wastewater is that sewerage will be pumped around the building – a myth Meeten assures is unfounded.

“All we’re talking about is it comes out of the wastewater pipe, it goes through a heat exchanger, and then it goes back into the wastewater pipe,” he says.

Meeten says the engineering behind using the thermal capacity of wastewater for heating and airconditioning is “remarkably simple”.

“What most commercial buildings do at the moment is have some form of heat exchanger on the outside of the building that sits up on the roof,” he says. “It is often something like a cooling tower, or it can be an air-cooled type of condenser.

“Whatever form it takes, all it is is a heat exchanger to either transfer heat out of or into the atmosphere. You’ve got lots of pipes which pump clean water around the building, which makes your air conditioning system work.

“The only difference between this model and using wastewater is it’s a different type of heat exchanger. Instead of one sitting up on the roof, this one will sit down somewhere perhaps buried under the ground, or housed on the ground. Instead of pumping lots of air through it to provide or remove heat, you pump wastewater through it so the heat goes into or come out of the wastewater.”

Wastewater is particularly suited to this task; with a stable and neutral temperature range (typically around 10°C to 15°C year round), it is often warmer than air in the winter (in colder climates) and cooler than air in the summer. Water is also an excellent conductor of energy, moving over four thousand times as much energy as air (for the same volume and temperature change). Water is a great conductor of heat, this is why it’s been used in central heating systems for centuries. Air is such a poor conductor of heat, we use it to our advantage as an insulator in things like double glazing and building insulation products.

A purpose-built heat exchanger is needed – however, a large portion of the infrastructure needed for the system is already exists.

“By far the biggest advantage I see is that the expensive below ground infrastructure is already there,” Meeten enthuses.

“The wastewater pipes are already in the ground. When you start looking at ways that cities can be more efficient, one of the things that often gets mentioned is district heating or district cooling. There’s no doubt that those sorts of systems are great and they’re very efficient, but to install one of those systems into your city means you have to dig up all the roads to put in the pipes, which can be very expensive.

“A wastewater system is making use of pipes that are already there.”

The ‘flow profile’ of wastewater is also well-suited to the purpose of heating and cooling buildings.

“If you look at the 24 hour profile of when wastewater flows, the amount of wastewater flowing at 2am when we’re sleeping is a lot less than 8am when we’re all up and working,” Meeten explains. “The flow profile matches very well to when buildings need their air conditioning systems working. I liken it to breathing – they both breathe in and out at the same time.”

Meeten describes wastewater as a resource no-one cares about – which is one of its strengths.

“If you want to use river water for this purpose, there’s all sorts of environmental issues you have to take into account,” he says. “Is it going to kill the fish eggs? Is it going to suck in insects? Those issues aren’t there with wastewater – nobody cares about it, it’s already contaminated, so there’s a whole load of things that you don’t have to worry about.”

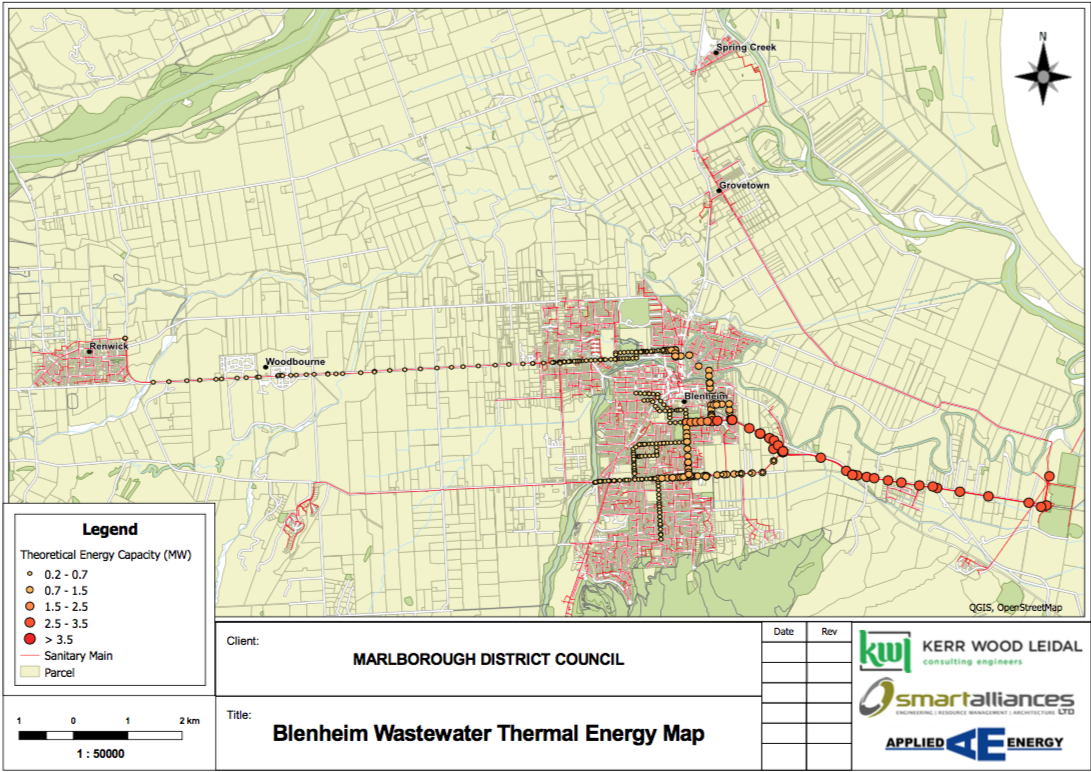

Computer modelling can be used to show on an energy map which parts of the city have a lot of energy available through the wastewater, and some examples of these will be shown in his presentation

Meeten says municipalities rolling out wastewater energy recycling projects are finding various models that allow them to make – at times substantial – new income streams.

“In one case from Canada, when applied to Melbourne it would mean an income every year of about $2 million; another model from Scotland could potentially raise $15 or 16 million a year when applied to Melbourne,” Meeten says.

Barriers

Meeten says red tape often has a chilling effect on wastewater energy recovery projects.

“The regulations for wastewater in some places were written back in the 1950s,” Meeten says. “Of course, back then we didn’t have the same understanding of climate change, growth of cities or urbanisation, and energy was really cheap.

“It was a different world when those rules and regulations were written. The main guts of those regulations – from a health perspective – are that buildings are allowed to put wastewater into a pipe, but you’re not allowed to take it back out again.”

Meeten says he has come across this problem in many parts of the world, including Australia, the US, Europe and Chile.

Communication between the building and wastewater industries – or rather, the lack of it – is also a problem.

“There’s a funny gap between people who work with buildings and people who work with wastewater, and normally these two never meet,” Meeten says. “I know that because I’ve spent 20 years designing buildings and now eight years working with wastewater. I’ve got a foot in each camp, but there’s very few people globally who work in this grey area in between.”

There is also a demarcation between the public and private sectors, with the buildings typically owned by the private sector, and wastewater infrastructure the remit of councils.

Although the rollout of projects in Australia has been almost non-existent, there has been some movement recently – the first wastewater project used for heating and cooling is currently being installed at the Australian Wool Testing Authority in Melbourne.

To hear Nick Meeten speak about harnessing wastewater energy, register for IPWEA’s Sustainability Conference, running 24-26 August in Melbourne.

The conference program is available – download it now.

Images: Courtesy of Nick Meeten

1. An apartment building in Canada heated with energy from wastewater.

2. Nick Meeten

3. A wastewater energy map