By: Jacob White and Tim Mumford

Unfortunately, project managers should be considering other factors beyond cost and schedule predictability.

Why unfortunately? Because these are harder to measure than traditional cost growth and schedule slip metrics.

What about effectiveness?

If we revert to a traditional metric of value- determination, such as Net Present Value (NPV) or Internal Rate of Return (IRR), we know that capital cost plays a pivotal role. More specifically, we know it answers questions that predictability metrics cannot, such as:

• Was it ‘value for money’?

• Did we spend more than was needed?

• What do others pay for this same scope as me?

• How do I know if my capital spend was efficient?

By example, if you spent 10% more than your peers on the same scope that delivers exactly the same benefits to citizens then this should be considered an inefficient use of capital funds. This concept of thinking about project effectiveness, and thus, success, is applicable on a project- by-project basis as well as a portfolio of capital works. On a portfolio basis, this puts your peers in an advantageous position; they can deliver more projects than you, for the same portfolio capital spend, per annum.

It is often contested that ‘going to market’ – or competitive bidding – is one method to get ‘value- for-money’, and thus ‘capital effectiveness’. If this is your position, then consider the following:

• Do the bidders price in unnecessary risk that you, the owner, are better placed to accept?

• Do you have a higher-than-normal amount of owner-overhead to manage scope?

• Is your organisation contractually difficult to interface with and is this being priced into bids?

• Are bidders’ proposals to deliver scope difficult to compare to one another?

• Are you using a contracting philosophy that appropriately assigns risk to the party that is best equipped to deal with such?

• Do you, as the owner, disconnect the bidder- procurement link and purchase equipment and bulk materials independently from the bidder?

• Do you frequently drop/add

scope or have a complex execution strategy?

• Are delivery specifications and requirements not documented and/or inconsistent?

• Is the scope of work fluid or is there

remaining risk in the project’s feasibility study?

If you answered “yes” to any of the above, there is a high probability that you are paying more than your peers for the same scope. As such, competitive bidding does automatically mean you’re ‘effective’ with your capital. This is due to the fact that bidders’ are pricing on

scope just as they’re pricing in unknowns, risk, and difficulty in management. All of these elements can be directly attributed to your project organisation.

For this reason, delineations of project success must consider cost (and schedule) effectiveness. If you have completed a project and do not have a critical understanding of what others would pay, or how long it would take them to complete the same scope for then this should be a focus for you.

Predictability is a difficult concept

Too often there is a perception that if a project’s budget is achieved, or even underrun, then we have achieved success. In reality, this culture often drives behaviour that we don’t intend; it creates a culture of conservatism and inefficiency.

Additionally, it goes against every notion of what project cost (and schedule) ranging means. In reality, a plus or minus 10% cost estimate means that half of the time we should be delivering scope for up to 10% more than we planned; the other 50% of the time we’re delivering 10% cheaper. This is a good example of how many organisations place emphasis on one element of predictability – namely consistency – above other measures. In reality,

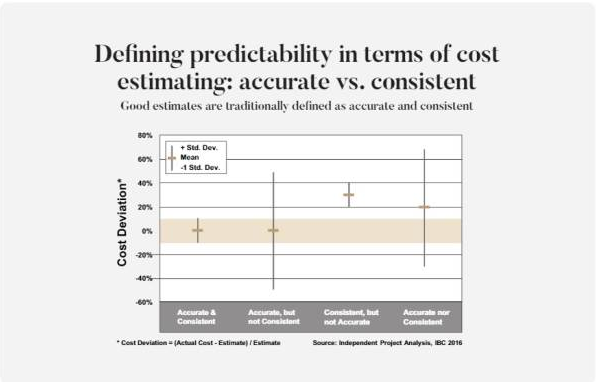

predictability of capital project portfolios should be considered in two dimensions [see below].

Predictability of portfolio cost estimates can be perceived in terms of accuracy and consistency. Specifically, portfolios can either fall in one of four categories:

• Accurate and consistent: where on average (mean or median) the portfolio was delivered as promised, and the variability of the project cost and schedule results were within initial expectations

• Accurate and inconsistent: where on average (mean or median) the portfolio was delivered as promised; however, individual project cost predictability was volatile

• Consistent and inaccurate: where on average (mean or median) the portfolio overrun or under

ran; however, individual projects were not volatile around this average

• Inaccurate and inconsistent: where on average (mean or median) the portfolio overrun/underran and at the same time the individual projects within the portfolio were irregular around this average

While most organisations probably have a notion of where they sit within these four categories, it is rarely documented or supported by any kind of detailed analysis. Further, measurements are often blurred by scope changes, variations in material quantities, or changes in project delivery. Timing of measurement can also be challenging when project budgets are revised or rebaselined. When you measure is equally as important as measuring like-for-like.

While methodologies that produce accurate and consistent cost estimates should be commended, it fails to consider whether value-for-money has been obtained. In an environment where predictability is favoured, councils (and taxpayers) should be asking whether too much money was spent to complete ‘that’ scope.

Or perhaps, could this portfolio be delivered for less money and if so, what other projects can be executed with the money saved?

The benefit of project appraisals

A key element that all the best performing project management organisations share is the ability to perform post-project appraisals. Post- project appraisals provide an independent, objective and measurable view of performance. Root causes behind that performance are also able to be fed back into the system. They’re more than an audit; they should be perceived as a critical step in closing the loop between project set-up and delivery.

To harness the full benefits, post-project appraisals should be completed quantitatively and methodically ensure accuracy, fairness and objectivity. The following areas influence organisation’s ability to obtain the full benefit from post-project appraisals:

Weak corporate governance and capital accountability

Most local councils do not have an independent process that provides a feedback loop of captured lessons learned (LL). The absence of a standardised approach and dedicated accountability for collection and distribution of LL impedes future best practice. By not capturing project history, challenges, decisions made, and benchmarks councils are missing a unique opportunity to improve future projects. Further, they’re setting themselves up, as an institution, to continuously make the same mistakes.

Lack of reliable data on industry norms

Without access to external information, organisations can only measure their performance against set targets. However, as mentioned earlier predictability does not mean competitiveness. To be competitive councils need reliable benchmark data from similar local and/or regional organisations.

Councils often cite lack of data, in terms of availability and quality, as a challenge to quantitatively measure project performance. The lack of effective and consistent tools to collect that project data is also an issue. As a result, appraisals are often qualitative or rely on poor quality data that limits accuracy and credibility. As a result, there is a reliance on near meaningless portfolio key performance indicators, such as “percent of projects delivered”.

Private industry differs. They’ve created tools to capture project data consistently; this helps them in their internal benchmarking efforts. They also utilise the data to measure their performance against their competitors through engaging an external third-party

bench-marking company. This third-party ensures independence; projects be measured and compared objectively and fairly. While they’re in different contexts, both private companies and councils have a similar priority: spend capital to maximise value and/or benefits.

Closing the loop

While there are systemic challenges for councils, most of the challenges identified can be addressed with a strong commitment from senior leadership to use post-project appraisals as

basis of continued improvement.

On a project team level, closing the loop on learnings from completed projects is vital. Costs should be reconciled, perceived economic benefit objectively and independently reviewed, and relevant data is captured in internal databases for future estimating purposes. Future estimating is reliant on sound estimating infrastructure, which is made up of:

• A formal estimating process that is bottoms-up, and aligns with historical (internal and external) data

• Planning to determine the interface between estimator and project team to establish schedule, resources, roles and responsibilities, estimating tools and agreed scope

• Documenting the basis of estimate (BoE) to ensure methodology, data sources and assumptions are clearly outlined

• Validating estimates (not simply reviewing)

The last bullet, validating vs. reviewing estimates, is a critical misunderstanding that needs attention before capital excellence is achieved.

Estimate review vs estimate validation

An estimate review is a qualitative process that looks at scope inclusiveness, assumptions in BoE and general structure of the estimate. Estimate validation, on the other hand, is a data-driven and quantitative process that examines the value for money of the estimate using metrics independent of those used to generate the estimate

This validation process draws on the collection of final project cost data. This data can be used to benchmark future project costs, and in turn, drive improved performance. To effectively validate estimates we need to consider the independence of data collected. For example: using a contractor’s estimate to validate another will not be a fruitful exercise (for many of the reasons noted above). Instead, the collection of historical data from a range of previously completed (and/ or estimated) projects would serve as a more appropriate basis to challenge assumptions. While this data can be sourced internally from auditing/reviewing historical projects, it is also beneficial to draw upon external sources. External sources are excellent at combatting ‘estimating self-bias’. Simply put: aiming and validating the same numbers leads to the same numbers. External sources provide a fresh benchmarking perspective.

Conclusions

This article highlights the importance of consistently collecting project data for the purposes of measuring current performance. Collecting, validating, determining trends and using these benchmarks to drive continuous should be a fundamental part of project systems. If we cannot measure the current value for money achieved on capital projects, how can we hope to improve?

References: Zhao, Y., 2016. Key Ingredients of Good Site-Based Estimates, Independent Project Analysis, November 2016

About the authors Tim Mumford and Jacob White, consultants at Independent Project Analysis (IPA) Australia, have critically evaluated the drivers and outcomes of more than 200 capital projects spanning a wide range of industries: infrastructure, manufacturing, oil and gas, refining and mining and minerals. These projects range in complexity (floating LNG to car parks) and have been executed over a wide-range of continents. Both Mumford and White have also analysed the drivers of successful portfolio management and project governance.

This story was first published in the April edition of IPWEA's member magazine inspire. IPWEA members receive an advance copy of the magazine.